What has the 9-Dash-Line to do with land plants? Nothing of course, no land, no land plants. But these days, science has to please (and serve) politics again as it used. Not only in the world's greatest monetocraty, the U.S.A., but also in its counterpart, the People's Republic of China, the emerging number 1, already in science and, in the near future, in general.

Until 2010, I was ignorant about how politics affect botanical reasearch. Well, contempory botany research. As somebody working with extra-tropical trees and their often, and long, debated species concepts, I was familiar with the one or other Italian pseudo-species erected by Michele Tenore [Wikipedia/IPNI] to support Garibaldi's One-Italia idea with dozens of new, Italian oak, maple, and other species (IPNI lists 924 plant taxa erected by Tenore; not all of them are pure fiction).

|

| Maple and oak species described by Tenore. Note the time match with the Italian unification and birth of an Italian nation. |

The idea is to demonstrate the richness and greatness of one's (very young, in this case) nation by the number of unique species it harbours. A sport very common among European botanists when the modern nation-states manifested at the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century.

A similar proud-citizen vigour is the reason for the many microspecies listed in the Flora of China [open e-access] many of which were invented in the 1950s to 1970s, typically named <Chinese place>-ense or -ensis, just so the – then still maoist-communist – young People's Republic of China would have their own species rather than just a population of a widespread species described by some imperialist European or Japanese botanist. A fashion revived in the last 20 years, coinciding with the rise of the PRC as a global player. Of the 16 endemic (and geographically very restricted) Chinese Acer -ense, a handful are re-recognizable species that can be confirmed by genetic data as well (notably including a recently, and very odd, phenotypically, described one: Acer yangbiense Y.S.Chen & E.Yang in 2003, see also Scientia-ex-machina... and Big Data = No Brain? Pt. 2). Of the 21 -ensis oaks (treated as two genera by the FoC) maybe two or three; for not few their ephemeral status as distinct species has been confirmed by molecular data (e.g. by their indistinct complete chloroplast genomes (which are, on the other hand, diverse within widespread species, see e.g. Li et al. 2025) and unspecific nucleome data; albeit the according papers pretend often, but not always (see again Li et al. 2025, super study not to miss out on), the opposite).

When nationalism is on the rise, endemism is, too. At least in plant names.

Confusing difference—when Chinese counties include Indian states

In 2010, we decided to have a go at a proliferate (European) pseudo-scientific approach for palaeoclimate reconstruction, the so-called “co-existence approach#rdquo; (CA) relying on an arcane data base (Palaeoflora Database, PFDB) that apparently was full of errors (Grimm & Denk 2012). We knew for quite a time that CA/PFDB estimates were extremely biased, converging to hot subtropical perhumid climates, and always, when there was an Engelhardioideae in the fossil flora list. The only openly available data were “mean annual temperature” (MAT) ranges for modern analogues of fossil taxa and we decided to assess their reliability.

To do so, we needed distribution and climate data, many species used in the CA/PFDB as modern analagues of fossil taxa today occur in East Asia, with a strong focus on the montane regions. A comprehensive altas (Fang et al. 2009) had just been published summarising climate parameters at county level for Chinese trees and shrubs extracted from a (walled) national Chinese plant distribution database. County-level means, they took the average climate value for the entire county, and then summed up those averages for all counties populated by a tree or shrub species.

Soon, we realised, we have to check and correct some of these ranges because for e.g. an Himalayan tree species, county-level data can be extremely off if the county starts at 1000 m a.s.l. in the monsoonal subtropical quasi-rainforests, where a lot of different plants thrive, and goes up to the alpine zone over 6000 m a.s.l., where few persist. We did this using Hijman et al.'s (2005) Worldclim database via the free software DIVA-GIS (Hijman 2004).

When doing so, I ran into another problem: The distribution (counties) as depicted in the altas didn't fit the lines in the political boundaries layer of DIVA-GIS as seen above. For a simple reason: being a state-funded and -issued publication, the Chinese-Indian border in the Fang et al.'s atlas wasn't the internationally used one – the Line of Actual Control, a colonial relict based on the McMahon Line in the eastern Himalayas) – but depicted the claim of the P.R.C. with the consequence that the Chinese counties in southeastern Tibet were much larger in the atlas than in reality because they included most of India's north-eastern state Arunachal Pradesh. An area that also features the lushest forests of the world, with more than 10,000 mm mean annual precipitation, hence, home to many tree species.

Schroedinger's species

A nice recent example for how nationalist policies effect plant taxonomy – a field of reasearch so utterly fundamental and nichy that it cannot have any political-propagandistic value (one may think) – are the beeches.

Traditionally, taxonomists distinguished one or two species in Western Eurasia (northern Spain to southermost Skandinavia to northern Iran), five species in China-Taiwan and two species in Korea-Japan, and one species in North America (Mexico, U.S.A., Canada).

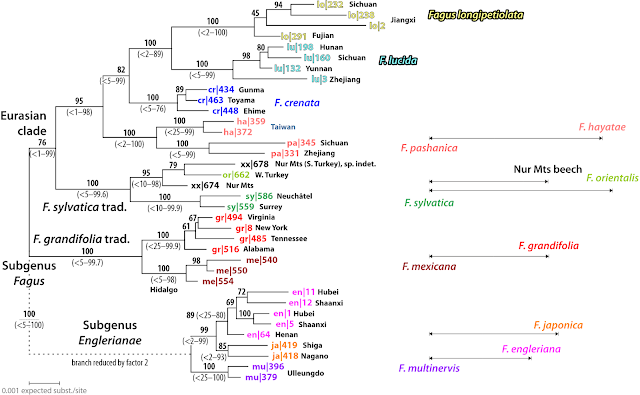

With the advent of genetic data, it became clear that this concept is too lumpy and that beeches fall into two subgeneric lineages and a complex assemblage of traditional species, phenotypically distinct, pseudocryptic species, species genetically distinct but phenotypically characterised mostly by clines or easy to overlook traits, and cryptic species, species that are phenotypically indistinguishable but genetically distinct (Denk et al. 2024):

- Subgenus Englerianae Denk & G.W.Grimm with three species in East Asia: F. engleriana Seemen in China and its cryptic Korean sibling (probably cousin) species F. multinervis Nakai and phenotypically distinct Japanese sister species F. japonica Maxim.

- Subgenus Fagus with

- a pseudocryptic species complex of four species in Western Eurasia: the western sister species F. sylvatica L., chiefly European, and F. orientalis Lipsky, south-easternmost Europe to the Pontic mountain range of northern Turkey; their Pontic-Caucasian sister-cousin F. hohenackeriana Palib.; and F. caspica Denk & G.W.Grimm, the beeches of the Talysh and Tabroz Mountains in south-eastern Azerbaidshan and northern Iran;

- five species in East Asia: the Japanese F. crenata Blume, the Chinese F. longipetiolata Seemen and F. lucida Rehder & E.H.Wilson, and the cryptic (pending in-depth morphological re-assessment) sister species F. hayatae Palib. (northern Taiwan) and F. pashanica C.C.Yang (across the montane Cfa zone of China)

- two pseudocryptic species in (eastern) North America: the Mexican relict species F. mexicana Martinez and its sister, the widespread (northern Florida to Ontario) F. grandifolia Ehrh.

The recognition of F. pashanica as a distinct species or not reflects changing P.R.C. political doctrines. The description of Fagus hayatae has been ascribed to the Russian (palaeo-)botanist Ivan Palibin [IPNI, Spanish Wikipedia, Swedish Wp]), and was published in a Imperial Japanese publication in 1911, the Journal of the College of Science, Imperial University of Tokyo (scan, so far, freely available via Smithonian BHL); the species being named in honour of the Japanese author of that publication, Bunzô Hayata [IPNI], a famous (Imperial-)Japanese botanist.

|

| Excerpt from Hayata's (1911) work. Note that Palibin's initials are wrongly reproduced. |

The paper is about materials for a flora of Taiwan—then a colony of the Japanese Empire. Populations of (seemingly) the same species were then found scattered across the mountain ranges of China. In 1978, the Chinese populations of F. hayatae were de-imperialised and recognised as a species on their own, published in the main Chinese botanical journal, the Acta Botanica Sinica (now Journal of Integrative Plant Biology; see here for its history).

With the opening of the P.R.C. to the world, a geobotanist from The Netherlands, Rob Peters, in course of his studies of beech forests across the world (Peters 1997), placed it, together with a Chinese co-author, as a subspecies of F. hayatae and published this in a PRC institution journal, the Journal of Wuhan Botanical Research (now Plant Science Journal). As such, as a subspecies of F. hayatae, it can be found in the Flora of China (distribution: Hubei, Sichuan, Zhejiang)

Cryptic but a good species

Genetic distinction, what we like to call “geno-taxonomy” of beech species is not trivial (cf. Denk et al. 2024), beeches are genetic mosaics and notoriously poor-sorted. There's probably not a single species alive that is not a bastard in origin, the product of reticulate evolution.

|

| Species coral of beeches. A complex history of speciation and evolutionary reticulation. After Schulze & Grimm 2022. |

Something that makes the interpretation of their phenotypes, traditionally how we define species and relate them with each other, tricky.

But with respect to their nuclear – mainly data produced by Jiang et al. (2021; see also Supplement S5 to Cardoni et al. 2022) and plastid – Worth et al. submitted, preliminary results available via Worth et al. 2021 – genetics, one thing is clear: the Taiwanese island populations consitute a much different genetic entity and resource than their continental counterparts. Fagus hayatae and F. pashanica are cryptic sister species with parly different evolutionary histories (cf. Denk et al. 2024). One, F. hayatae, is (today) endemic to northern Taiwan (a sister plastome has been detected in a F. lucida from south-eastern China), genetically isolated and drifted; the other endemic to the P.R.C., where its ancestors mingled longer with other, sympatric beech species. And the two had much different last common mothers.

However, with president-for-life Xi's strong focus on the One-China and 9-Dash-Line policies, contemporary P.R.C. research has to ignore even strong, compelling evidence for recognising two genetically clearly distinct species in (continental) China and (insular) Taiwan as illustrated in the tree and map provided by Jiang et al. (2021), the research group who produced the compelling evidence to seperate the two species.

How we know they had to follow state doctrine rather than scientific evidence? Jiang et al. discuss in detail and question the traditional, too lumpy species concepts for the North American (2 spp., traditionally perceived as one, depicted as two in their fig. 1) and Western Eurasian species (4 spp., traditionally 1–2, also depicted as two), as well as the case of F. multinervis of subgenus Englerianae, a Korean island population in the Sea of Japan, phenotypically indistinguishable from the common in China F. engleriana (Jiang et al. 2021, section 4.2 entitled “Species delimitation of three segregates within Fagus”).

But ignore the forth potential “segregate” apparent from their data. They don't even mention F. pashanica or F. hayatae subsp. pashanica (C.C.Yang) R.Peters & J.Q.Li. The very species once described to rid China from an imperialist taxonomy; and now confirmed as a good and valid species! What once would have made the P.R.C. proud, is now impossible to mention: There shall not be a Chinese-Taiwanese “segregation” in a P.R.C.-led and -financed publication in the 21st century, not even in a tree genus no-one really cares about (except for a few people with particular taste).

And then, there's of course the inlet in the map used in a follow-up paper in another “international” journal.

Treating Taiwan as a province of China – note the absence of the actual line of control in the Taiwan Strait seen in non-P.R.C. maps, while there's a prominent line east of the island and the missing islands north of Taiwan, controlled by Japan and claimed by Taiwan (but not the P.R.C.) – follows international customs. Taiwan is a de-facto independent state that has no legal right to exist, Schroedinger's state. A situation imposed by the U.S.A. in 1971 to appease the P.R.C. and to draw it away from the then still existing Soviet Union. These days enforced by trading benefits from the not-so-communistic-anymore (remind you, communism means everything belongs to everyone, billionaires and private-owned mega-companies are an impossibility) People's Republic (by 2025, only 12 countries are left that recognise the statehood of Taiwan).

So far, so fine. But the inlet depicting “China” at large is blatant state propaganda. All those little poorly resolved but oversized dots towards the south are the Spratlies and Paracels, disputed reefs and tiny (now including artificial) islands scattered across the South Chinese Sea (a short intro by the BBC), lovingly embraced by the 9-Dash-Line. A large oceanic area completely devoid of anything even remotely reminescent of a beech forest. However, in contrast to Fang et al. (2019), they seemed to have overlooked Arunachal Pradesh…but times are changing. Hindu-nationalist Modi's India is a partner, member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, a collective of anti-Western autocratic regimes, as well as a worthy competitor. While those other countries surrounding the South China Sea are mostly the latter (and have no nuclear weapons).

State propaganda published in Plant Diversity, an Elsevier “international plant science journal” with an impact factor of 4.6., which puts it in the grant-relevant upper quartile of its field (so-called “Q1-journals”

The long arm of the CCP

Would authors have a choice to not show the pointless – from a (geo)botanist and biological point of view – assemblage of tree-free islets and the 9-Dash Line? I guess not. Plant Diversity may be distributed by Elsevier, a highly profitable global player originating from The Netherlands owned by RELX (generating near 2 billion net income [company-PDF]), but it's a Chinese-run journal from the Kunming Institute of Botany.

Jiang et al. (2021) was published in the Journal of Systematics & Evolution, distributed by Wiley (U.S.American) but a P.R.C. journal, too.

One cannot blame high-level Chinese (chief-)editors of state-funded journals and common researchers publishing in their journals (or forced to) obeying to P.R.C doctrine: the P.R.C. is a capitalist-collective-hybrid dictatorial state with strong tendencies to become an absolute monarchy (see e.g. this free-to-access long-read in the LA Times). It controls its people regarding all aspects of life and society (see e.g. this 2-piece documentary on TikTok airing on Arte, French-German only; or the pretty comprehensive Wikipedia article on their “Social Credit System”). It's not surprising that such a regime uses its scientific outlays for its political agenda as well.

But what about the free-world, fact-oriented editorial policies of “international” journals and Western-democracy enjoying science publishers distributing them? International are the boards of topic editors of both J. Syst. Evol and Plant Divers., plenty of free-world scientists supporting the P.R.C.'s claim on the entirety of the South Chinese Sea (and Taiwan; it'd not be an aggression violating international laws to attack a piece of land governed by a not-recognised state, would it?) Otherwise they couldn't work for those journals for free, could they?

Make a stand against agressive-territorial political propaganda? Can't do. Already 2020 China was by far the most proliferate, largest science nation; publishers much benefit from its output and generated impact, the number of citations. Plant Diversity's astonishingly high impact factor (noting what research published there, such as the Li et al. 2023 paper) is a witness of that. And career scientists, especially in the West, are hooked on impact like junkies on Crystal Meth.

Letting pass a little bit of political propaganda as a non-dependent topic editor and reviewer isn't a big deal; no one gets hurt by nine dashes in a map (except maybe for Philippine fishermen at some point). Neither is that an increasing number of Chinese-funded and “internationally” peer-reviewed research not only focusses on Chinese plants, but relies – or has to rely, to get funding?! – on a sample chiefly restricted to the borders of the P.R.C. (including Taiwan, naturally). Even when the objective of the paper is to, e.g., reconstruct the phylogeographic history of a plant lineage found across the entire Northern Hemisphere.

Let's make scientific nationalism fashionable again

For my part, I'm very much looking forward to see the first paper published on some “U.S. American” plant. For instance, looking at Platanus (plane trees) with their distribution around the “Gulf of America” and proposing to treat P. mexicana as a subspecies of the “chiefly U. S. American” P. occidentalis.

|

| How to secure a NSF grant in the next 4+ years: Denk et al. (2012), Fig. 4, updated the P.R.C. way to make America great again. |

Just to get funding from the Muskists-supervised NSF. Make propaganda science again!

PS Emigrating to the P.R.C. may be an option in this case. Although there's not a single (native) plane tree species in Taiwan, not to mention the Paracels and Arunchal-Pradesh. But Vietnam, the land directly west of the nine dashes used to be a Chinese province, too. Their only native plane tree species, sipping across the border, P. kerri [Wp-stub/GBIF distribution map] is one of the many extra-tropical tree species that are severly understudied.

Cited works

No comments:

Post a Comment

Enter your comment ...